Kourosh Ziabari – Asia Times: It is common knowledge that the Iranian government is in an acutely vulnerable position and that a blend of draconian international sanctions, public discontent at home, corruption and unremitting power struggles have drained its resources and resilience, stripping it of political leverage on the world stage.

To the constellation of the Islamic Republic’s adversaries and opposition parties in exile, this fragility presents a unique opportunity to prey on and see if a coup de grace can be administered to what appears to be a languishing, heavily wounded antagonist.

One day, a terror attack is orchestrated in the restive south of the country and when the suspected mastermind is arrested to stand trial, spin doctors saturate the media with cries that he was an innocuous journalist targeted by the “regime” because of his dual nationality.

On a different occasion, the lumbering Iranian reform movement comes under fire from the well-heeled troll armies because of how it has thwarted frequent regime-change plans over the years.

Another day, distinguished names of the community of Iranian-Americans are earmarked for calumny because in their public narratives, they don’t paint the country as a dungeon of misfortune and agony.

Even the country’s two-time Academy Award–winning director Asghar Farhadi is not spared from smear campaigns, for the nuances with which he portrays the state of life in Iran contradict the voguish sacrosanctity that Iran is the worst, most terrible place in the world to which democracy should be urgently and forcibly exported.

But even if sanctions, solicitation of foreign military intervention and non-stop media hype have not catalyzed the disintegration of the nation-state, there are always new options to navigate to induce that ideal, particularly given how confused and incoherent the government in Tehran seems to be in dealing with a slew of conundrums.

Of course, a convenient blueprint would be to disparage the cultural heritage of the nation, documented to be nearly 7,000 years old, a corporality that makes millions of Iranians proud at a time when they don’t have many reasons to feel sanguine.

In a theocracy where a plurality of officials have cemented their revolutionary credentials by bad-mouthing the idea of national identity and pre-Islamic history and squared up to the country’s ancient civilization, begetting a hollow dichotomy of religion versus nationalism, which means cultural heritage is already endangered, it comes across as a low-cost strategy to blitz every tradition, rite, name and personality that point to antiquity – a history that no authority is tasked with safeguarding.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a “human-rights activist” ventures to describe the Persian New Year celebration, Nowruz – a centuries-long occasion on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity with a dedicated day on the United Nations calendar – as a trigger of violence.

Similarly, you shouldn’t be taken aback when the women’s rights celebrity of that same Persian-language broadcaster defames Ferdowsi, the 10th-century epic poet glorified as “the Homer of Persia” by Sir William Jones in 1799, as a misogynist.

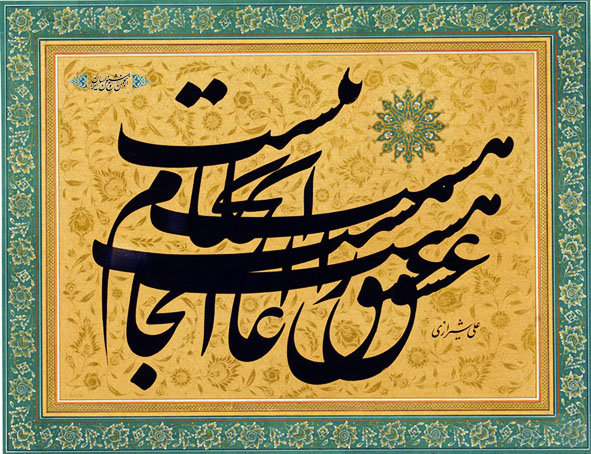

Demonizing modern Persian

Fueling separatism in a country that is a kaleidoscope of ethnic groups and lingual minorities is another handy alternative, and to play the ethnicity card efficiently, why not cherry-pick the modern Persian language, the national language of Iran and the lingua franca of Iranian minorities since AD 800, and attempt to cannibalize it?

Persian language functions as a binding force that has maintained the human and cultural connections of Iranians of all stripes and religious, ethnic backgrounds and sociopolitical leanings for centuries.

It is true that the passage of time and wax and wane of Iranian society, particularly since the Arab conquest of Persia in AD 633, have impinged on the purity of this historical artifact and metamorphosed it by converting its vocabulary into a hybrid of Arabic, Greek, English, French and Russian loan words coupled with a watered-down rendition of Old Persian, but it is still a highly lyrical and proverbial parlance that inspires thousands of speakers and learners.

Now, a campaign has been set in motion on social media, characterized by the hashtag “ManoFarsi” in Persian transcript, meaning “me and Persian,” and members of Iran’s ethnic minorities are encouraged to share their “bitter experiences” of living and growing up under the linguistic dominance of the Persian language and the episodes of discrimination and humiliation they have gone through for being born in Iran speaking languages other than Persian.

The schemers of the campaign are the Persian-language broadcasters in Britain and the United States that have particularly appealed to Iran’s Azeri, Arab, Kurdish and Turkmen minorities to amplify their resentful voices of how the Persian language has been used to hegemonize them and subdue their cultural and ethnic distinctions.

Hours of airtime have been consecrated to launch caustic attacks on the Persian language, slur the towering figures of Iranian literature and impeach the Iranian government for its language policy, which mandates that education and administration should be conducted in the nation’s official mode of communication.

Heaps of tweets carrying the hashtag “ManoFarsi” have been posted within a span of two weeks, making it a hot trend nationally and internationally.

On the surface, the bandwagon gave an inkling of a sincere attempt to incentivize debate on Iran’s language policy and also gave a pulpit to the nation’s minorities to reflect on how they believe their linguistic and cultural nuances have been obscured by the supremacy of the Persian language in a country that is a melting pot of cultures and ethnicities.

But it soon transpired that the online thrust was another ruse in the playbook of individuals and entities with little to zero sympathy for the well-being and fundamental rights of Iranians to sow the seeds of discord in a society that is still co-existing despite deep political, ideological and economic fissures, and experimenting with a new means of pulverizing the integrity of a country whose leadership is visibly passive and tenuous.

By delicately building on the language-education conversation to extrapolate that the Islamic Republic has repressed ethnic minorities and therefore they need to be granted sovereignty, and by appealing to the ethnic sentiments of the minorities and whipping them up to claim rights that might be fulfilled outside the geographical boundaries of Iran, the spearheads of “ManoFarsi” are normalizing patterns of thinking that are plainly dangerous.

Mixing fact and fiction, resorting to false information, neglecting the certainties of Iran’s ethnic makeup and making fallacious generalizations have been the hallmarks of the “me and Persian” colloquy.

An early conclusion by any impartial observer would be that there is no reason to attack a language with roots in ancient history, noted for its role in cultivating masterpieces of poetry, prose and romantic and mystic literature, unless there is a political machination at work.

That the residents of peripheral cities, minorities and ethnic groups are treated less favorably and have a smaller share of power and government vacancies as compared with the capital-dwellers is a given, but it is not because the establishment wishes to mollycoddle the Persian language and has a special favor in what the Persian concept stands for; otherwise, there wouldn’t have been instances of high-ranking authorities and public figures excoriating the nation’s cultural heritage and pre-Islam grandeur publicly.

So to put Persian language on trial for vanquishing the linguistic diversity of the nation is shortsighted at best, if not malicious.

Also, the reality of life in Iran is a bit different from what is insinuated by the “ManoFarsi” activists. It is easy to take a day trip to the country’s Azeri- or Kurdish-speaking provinces and figure out whether the Persian language is a force of authority or a marginalized jargon.

Indeed, local publications and broadcasters publishing material in these languages, or the provincial authorities making their public speeches and statements in non-Persian tongues, may not be sufficient barometers of the influence of vernaculars, but to remedy the perceived underrepresentation, it sounds malignant to encourage people to repudiate their entire national belongings and rise up against the “Persian-speaking oppressors.”

It is a persuasive idea to promote education in local languages so that minorities feel valued. This is something the government has promised for quite a while would be fulfilled. But it is far from reasonable to proselytize the ill-conceived mantra that Persian has been used as a weapon of subjugation to clobber the minorities, and pit different groups of people against one another along ethnic and linguistic lines.

There are countless examples of how countries with multiethnic compositions have not rubber-stamped the use of local languages in executive affairs and education. For centuries, the French government has sculptured a language policy based on the idea of “one nation, one language” and its constitution stipulates that French is the “only language of the republic.”

If you don’t like the French analogy on the account that France is a democracy while Iran is not, take Nigeria, a country in which nearly 500 languages are spoken, but the government recognizes only Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo as official languages.

Provocateurs guised as the patrons of the Iranian people sometimes find it difficult to abstain from the euphemism that often marks their messaging and narratives, but maybe they are trying to imply that it is OK if, to dismantle the Islamic Republic, the geographical reality of Iran is also decimated, and don’t mind if this sort of discourse comes into view as separatism.

Those who have found the “ManoFarsi” campaign an opportune moment to score political points haven’t responded to the question why they continue to tune in to opposition broadcasters whose programming is 100% in Persian.

They also refuse to acknowledge that they won’t be served at bars, restaurants and shopping centers in London and Los Angeles if they approach the salespeople and speak in their mother tongue, so they need to learn and speak English. But the chicanery used to fuel the campaign underlines why this debate is not really about language education.