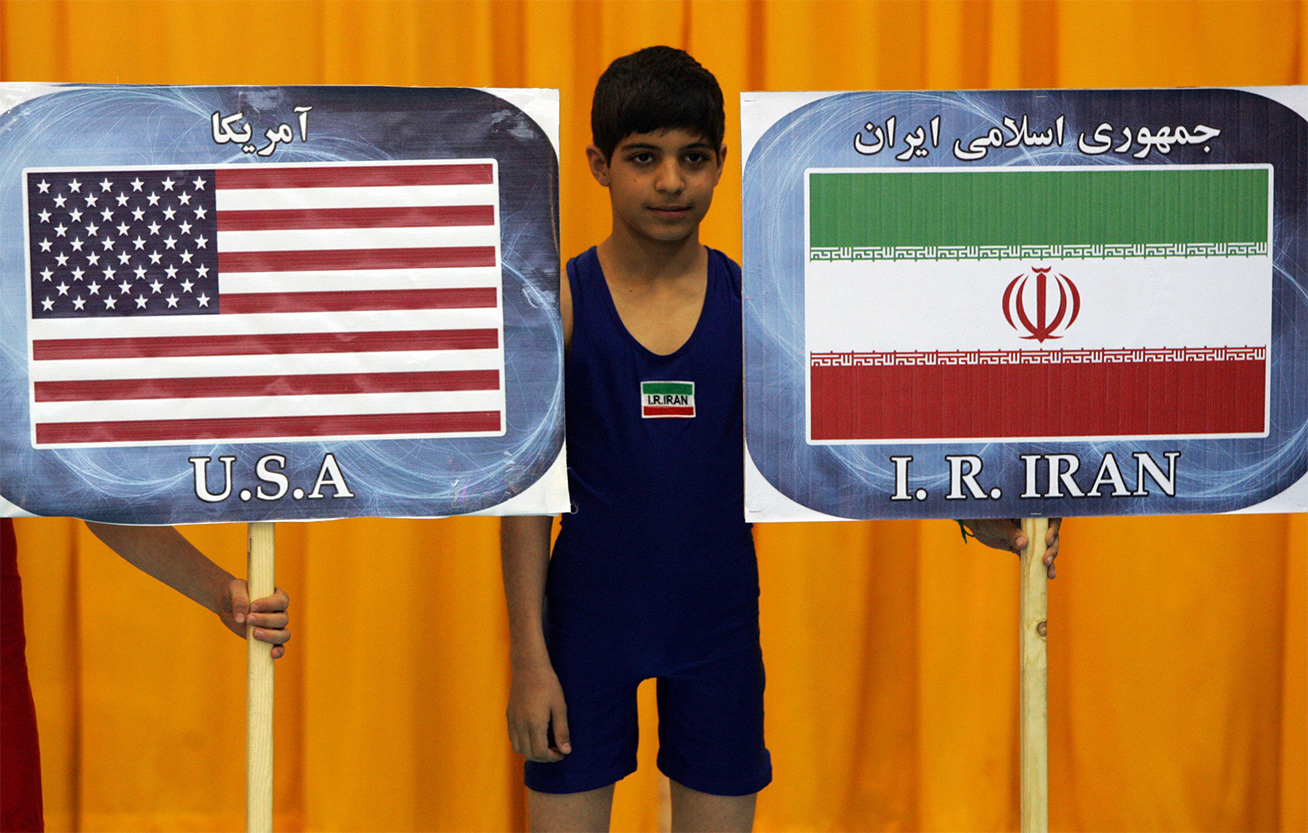

Kourosh Ziabari – Asia Times: Iran-United States relations are on the ropes again after a much-anticipated wrestling competition between the two national sides was abruptly canceled.

In late 2021, it was announced that the national wrestling teams of Iran and the US would be facing off for a friendly match in February next year.

Many observers of Iran’s politics were overjoyed in the hope the apolitical encounter would build bridges between the two rivals, whose recent engagements cannot be characterized as “friendly.”

Iran and the US have not had formal diplomatic relations since 1979, but in defiance of the official narrative of the two governments built on maintaining and prolonging hostilities, punctuated by fleeting episodes of rapprochement, their people bolstered unofficial bonds.

The presence of a sizable community of Iranians in the US, including nearly 12,000 international students, played a role.

Throughout these jarring years, academic, cultural and athletic exchanges remained largely unaffected by the virulence toxifying the political relationships of the two foes. But these events haven’t been as vigorous and lively as they once were before the 1979 uprising in Iran that dislodged a US-backed regime from power.

However, when the Islamic Republic of Iran Wrestling Federation decided earlier this month to call off the much-hyped bout slated to be held in Arlington, Texas, on February 12, hopes were dashed that some dialogue, at least on the wrestling mat, was within reach.

But under an ultra-conservative administration in Tehran, the fissures became clear and the Iranian side withdrew after the US government denied visas to five members of its delegation.

Gold medalist denied entry

One of those whose visa application was turned down was Alireza Dabir, the head of the wrestling federation and one of the nation’s eminent wrestlers, whose medal haul includes a 2000 Summer Olympics gold.

Although the State Department and Homeland Security do not publicize the grounds on which visa applications are rejected, the dominant talking point locally is that Dabir couldn’t get his entry pass to America in retribution of the incendiary remarks he made in a televised interview in January, where he used the slogan “Death to America,” a favorite refrain of hardliners.

“I always say, we chant ‘Death to America,’ but what is more important is the action. Even the physician who wears a necktie, but is doing his job well, in my view is saying ‘Death to America,’” he said in the controversial interview.

It is not possible to verify a direct connection between Dabir’s remarks and the denial of his US visa, but he had made clear closer to the February 12 contest that in the likely event the US government refused a visa to any member of the Iranian outfit, his federation would drop the trip altogether.

Members of the Iranian opposition in exile, who relish the country’s increased isolation, celebrated the cancellation of the event with schadenfreude. Many of them, including defectors from the national wrestling team who once competed under the flag of the Islamic Republic, had campaigned for weeks to persuade US authorities to stop the contest.

Iranian hardliners whose domestic economic monopoly is best safeguarded with the nation’s persisting detachment from the outside world, and opposition factions who continue to vie for their share of power in a new political setup, converged and slung mud against improved Tehran-Washington relations.

So the cancellation of a friendly wrestling match that could partly extricate the beleaguered nation from isolation would be glad tidings to them.

Recrimination overshadowing relations

An Iranian-American academic said the canceling of the match pointed to the broader trend of recriminations overshadowing Iran-US relations.

“Both Iranian and American elected officials and policymakers who believe that some degree of rapprochement in diplomacy between the two nations would benefit their respective national interests face a daunting obstacle in the reductive, stereotypical and overwhelmingly negative attitudes their societies widely harbor for one another,” said Robert Asaadi, an instructor in the Departments of Political Science and International Studies at Portland State University.

“The domestic constituencies in both countries primed for conflict are sizable and constitute clear majorities, therefore elected officials in both countries are incentivized to behave accordingly.

“The canceled wrestling match seems to be the most recent fodder for this ongoing politics of antagonism,” he told Asia Times, alluding to a 2021 Gallup poll that found 85% of Americans held an unfavorable view of Iran, mirrored by similar IranPoll data gauging negative attitudes of the United States among Iranians.

But some analysts don’t pin the blame for the unfortunate state of relations entirely on the anti-US stance of the Iranian authorities.

“I do see the rhetoric of some Iranian officials as quite harmful. However, it is important to note that American officials are also not innocent bystanders,” said Mona Tajali, an associate professor of international relations and women, gender and sexuality studies at the Agnes Scott College in Atlanta.

“I see that there are forces on both sides who aim to harm or hinder dialogue and fruitful exchange among the populations.

“The US sanctions on Iran have also negatively affected many Iranian artists, athletes, academics, students and more. One of the most fundamental ways was, for example, restrictions for travel and receiving visas during the Muslim Ban era of the Trump administration,” she added.

Opportunities lost

It is not the first time that rhetoric by officials in both countries killed off any opportunities for track two diplomacy, disappointing professionals who had worked to patch up the differences through artistic, cultural and sporting activities.

In February 2009, when 12 US women badminton players planned to go to Iran on the initiative of President Barack Obama to compete in an international competition as well as send a message of friendship to the Iranian people, the hardline administration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad denied them visas, and Obama’s outreach was thwarted.

Ahmadinejad’s eight tumultuous years in office, coinciding with the latter years of the George W Bush presidency and the early part of Barack Obama’s term, brought the nascent unofficial, people-to-people diplomacy to a grinding halt.

In December 2006, his government sponsored the International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust, featuring former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke and other notorious white supremacists.

The provocative conference caused many European states, as well as the United States, to fundamentally reconsider their interaction with the Islamic Republic. Iran did not relinquish its newly-adopted Holocaust denial bombast in the years to come, irritating the West.

The departure of Ahmadinejad and the entry of moderate Hassan Rouhani in 2013 started a transition in the course of relations as the new administration recognized how significant it was to scrap the legacy of dissension and move toward confidence-building.

But still, Rouhani did not make all the decisions in Iran’s labyrinthine power structure, and continued Tehran-Washington animosity had vocal advocates.

Indeed, President Obama’s tenure was missed opportunities for diplomatic fence-mending. In a March 2015 message on the Persian New Year, Nowruz, Obama said that year represented the “best opportunity in decades” to settle the differences between the two countries, adding “this moment may not come again soon.”

A nosedive after Trump

Despite the hardliners in Tehran, the historic Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was clinched later that year and the first signs of increased Iran-US ties emerged. But the momentum gathered was short-lived and Obama’s successor Donald Trump pulled the US out of the deal with the stroke of a pen in May 2018.

Relations have been nosediving ever since.

Shireen Hunter, an honorary fellow at the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at the Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, told Asia Times that under the current political climate, expecting a rejuvenation of Iran-US mediation would be idealistic.

“I don’t see any possibility of a track two diplomacy flourishing between Iran and the US in the near future. The current hardline government appears to be opposed to any dealings with the US, official or unofficial,” she said.

“However, if a mutually acceptable agreement on the nuclear issue is reached between Tehran and Washington and is followed by gradual engagement of American companies in Iran, other collaborative exchanges, including between Iranian and American artists and athletes, could also increase,” she added.

According to Hunter, the adverse effects of the Islamic Republic’s official anti-Americanism on ordinary Iranians are too enormous to measure: “All those Iranians who have any concern for their country’s future realize the damaging effects of the continued stalemate in Washington-Tehran relations for Iran.

“Whether the hardliners, which now control the government, would have the courage to pursue reconciliation with the US is hard to say. However, if they decide on this course of action, they are more likely to succeed than the moderates were, since hardliners would not face opposition from the moderates in reaching out to Washington,” she said.

The only eventuality from peddling a fierce anti-American ideology will be that Iran will continue to feel cornered, even if it does not admit it, and suffer a loss of credibility when its mostly pro-Western interlocutors in the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific call it a counterproductive narrative.

Ali Ansari, a professor in modern history at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, says the antagonistic discourse against the US harms Iran’s public reputation: “It is often a reflection of the need to play up to the official ideology and may have some traction on the street, though not necessarily the Iranian street, and it is certainly not in Iran’s wider national interest.

“My own sense is that the political atmosphere will continue to be difficult. It is completely different to what we experienced in the [former Iranian President Mohammad] Khatami period, and even that was not easy. Khatami understood that the wall of mistrust would have to be removed brick by brick. Now despite or even because of the JCPOA, the wall may even be a bit higher,” he told Asia Times.

This interview was originally published on Asia Times