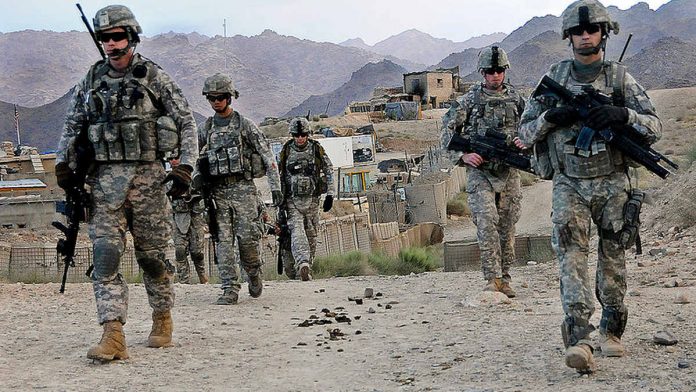

Kourosh Ziabari – Asia Times: As the sun sets on America’s costly 18-year war in Afghanistan, neighboring Iran is poised to gain an upper hand as foreign troops chart their withdrawal from the war-ravaged country.

That is despite Tehran’s vehement vocal objections to a nascent peace deal between the US and Islamic fundamentalist Taliban group aimed at ending a war that by some estimates has cost American taxpayers nearly US$2 trillion.

In February, US President Donald Trump’s administration and the Taliban reached a conditional agreement following nine rounds of intense negotiations in the Qatari capital of Doha.

The deal covers four key issues: a sustainable ceasefire, facilitation of intra-Afghan talks now underway in Doha, counterterrorism assurances including a Taliban vow to break ties with al-Qaeda, and withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan within 14 months.

On March 1, Iran’s Foreign Ministry was critical of the agreement, claiming it legitimized the US’ presence in Afghanistan. “The United States has no legal standing to sign a peace agreement or to determine the future of Afghanistan,” read a statement by the foreign ministry at the time.

Experts, however, see that the Islamic Republic’s opposition to the peace accord as more histrionics than substance in light of its burgeoning ties with the Taliban. They say any commitment by the US to pull its forces out of Afghanistan will bode well for Tehran, laying the groundwork for it to expand its influence in a neighboring country where resentment against Washington is rife among ordinary citizens after nearly two-decades of occupation.

“Iran has rejected the Doha accord because they can’t be seen to officially endorse or support any agreement that involves the United States. However, within the corridors of power in Tehran, the regime is no doubt satisfied that the US does appear intent on withdrawing at some stage in the near future,” said Dr Sajjan Gohel, international security director of the London-based Asia-Pacific Foundation.

“There have been concerns for years that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) have adopted a flexible and pragmatic approach with the Taliban. On occasions, this has translated into providing clandestine assistance in terms of resources and bomb-making equipment which has been used to carry out attacks against coalition troops,” Gohel, also a visiting lecturer at the London School of Economics and Political Science, told Asia Times.

Iran and the Taliban are now inching closer to becoming reluctant bedfellows. However, their dalliance follows an onerous history of rivalry, culminating in a rollercoaster ride in relations since the late 1990s.

On August 8, 1998, Taliban insurgents captured the Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif and then assaulted the Iranian consulate in the besieged city, where they took a number of diplomats and civilians hostage. Eleven Iranians, including a journalist with the Islamic Republic News Agency, Mahmoud Saremi, were assassinated.

Iran vowed retaliation and deployed some 70,000 soldiers as well as 150 tanks along the porous border with Afghanistan. A full-blown military confrontation with global spillover effects was in the offing.

Last-ditch diplomacy spearheaded by Iran’s then-president Mohammad Khatami and UN special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi persuaded the Taliban to release 26 Iranian prisoners and promise punishment for the renegade members of the group responsible for the massacre.

In 2001, in the wake of America’s initiation of the global war on terror, Iran furtively teamed up with the George W Bush administration to oust the Taliban regime from power and lay the groundwork for the installation of a democratically-elected government.

The same year, Tehran and Washington collaborated on securing the Bonn Agreement under the auspices of the United Nations to fast-track the process of state-building and the repatriation of Afghan refugees.

According to Ryan Crocker, former US ambassador to Afghanistan and Iraq, Iran’s slain commander Qasem Soleimani, who was eliminated earlier this year in a US drone strike in Baghdad, was part of rare and high-stakes US-Iran negotiations following the 9/11 attacks that sought ways to vanquish the Taliban, as well as identify al-Qaeda strongholds and masterminds in Afghanistan.

The Taliban, driven by an orthodox anti-Shiite ideology, had earlier been engaged in full-blown persecution of the Hazara people, a Shiite, Persian-speaking ethnic group native to central Afghanistan who are presumed to be culturally tied to and inspired by Iran.

Anywhere between 2,000 and 20,000 Hazaras are believed to have been summarily executed by the Taliban in 1998. It wasn’t unique in history: A campaign of harassment against the group reaches as far back as the late 1880s, when Amir Abdur Rahman Khan was the Emir of Afghanistan.

The dictator sold thousands of Hazaras into slavery and close to 60% of their total population at that time were decimated under his watch.

Seeking protection and more dignified lives, Hazaras in their thousands pinned their hopes on neighboring countries, and flocked to Pakistan and Iran. The majority of the 2.5 million Afghan refugees living in Iran today, including undocumented immigrants, are Afghans of Hazara descent.

Historically, Hazaras have fought in Iran’s wars and been regular pilgrims to holy Shiite sites in Mashhad and Qom, underscoring the cultural affinity between Iran and the minority. In the 1980s, when the then-Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Iran, General Esmail Ghaani, the current commander of IRGC’s Quds Force, mobilized thousands of Hazaras to fight for Iran in that bloody war.

Capitalizing on their disillusionment with and grievances against the Taliban, the IRGC has been able to recruit thousands of Afghan youths, including Hazaras, to marshal the Fatemiyoun Brigade, numbering between 10,000 and 25,000 soldiers, for combat in extraterritorial missions including the Syrian war.

Sources close to the military force have revealed at least 2,000 Fatemiyoun fighters have been killed in Syria after putting their lives on the line to save the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad and battle the Islamic State (ISIS). A further 8,000 have been wounded in the fighting. Many of these militia “volunteers” are buried in Iran.

When then-president George W. Bush lumped Iran into an “Axis of Evil” alongside Iraq and North Korea as the states most perilous to world peace and security in a 2002 State of the Union address, an earlier embryonic rapprochement between Iran and the US was nipped in the bud, coaxing the Islamic Republic to reconsider its regional calculus, including its relations with the Taliban and Afghanistan broadly.

With the rise to power of hardline Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a former mayor of Tehran, as the president of Iran in 2005, hostilities with Washington spiraled, and the immediate eviction of US and NATO troops from Afghanistan became a catchphrase of Iranian authorities, who found themselves echoing the Taliban’s line.

In May 2007, as Iran and the US were busy trading barbs, then-vice president Dick Cheney warned Tehran that Washington would utilize its naval power to strike Iranian targets if Iran threatened US interests. IRGC’s commander General Mohammad Ali Jafari retorted by saying that if attacked, Iran would pound US assets and bases in the region, including in Afghanistan.

Then-secretary of defense Robert Gates revealed to the media a few weeks later that the US had detected “insurgents in Afghanistan” obtaining large shipments of arms from Iran, including parts required to produce explosive projectiles.

Ever since, reports have surfaced from time to time pointing to Iran’s military cooperation with the Taliban, including in February this year when the police chief of Afghanistan’s Uruzgan Province, General Muhammed Haya, disclosed that the IRGC had supplied the Taliban with anti-aircraft missiles.

Houchang Hassan-Yari, a political scientist and professor emeritus in the Department of Political Science at the Royal Military College of Canada, says Iran and the Taliban have shared interests and will consent to a “marriage of convenience,” even though they may go separate ways ideologically.

“[The] Islamic Republic and Taliban have a reciprocal need. It is a marriage of convenience [which is] realistic, despite their doctrinal divergence. Both use these relationships as an instrument of pressure on their enemies,” Hassan-Yari told Asia Times.

“A government of national reconciliation that includes the Taliban will be welcomed by Tehran. We must not rule out the emergence of such a government in Kabul following the Doha negotiations, unless Washington opposes it,” he added.

Hassan-Yari sees Iran’s three major objectives in Afghanistan as follows: the departure of American soldiers, who are viewed as detrimental to Iran’s survival; bringing to power a friendly government in Kabul that refuses cooperation with the US; and maintaining influence with Afghanistan’s Shiite community, who reside close to Iran’s eastern border, which it hopes can function as a buffer zone between it and the rest of Afghanistan.

“For the achievement of these objectives, the Islamic Republic is ready to do anything, including working closely with the Taliban and corrupt Afghan politicians,” he said.

One of the terms of the US-Taliban deal is the latter’s commitment to ending violence, for which the US has vowed to slash its troop levels of 4,500 to 2,500 by mid-January 2021 and then to zero in a 14-month timespan.

Trump’s demarche is facing congressional opposition, even among Republican party leadership, with Senate leader Mitch McConnell objecting on the basis that a premature withdrawal would “hurt our allies and delight the people who wish us harm.”

In any case, a fateful US military withdrawal, whenever it happens, will leave behind fertile ground for Iran to consolidate a foothold and add Afghanistan to the list of countries in which it maintains a formidable proxy presence as it maneuvers to promote its influence and religious ideology.

Gohel says with the US withdrawal, “it is likely that Iran will use the opportunity to consolidate its already significant influence in the western parts of Afghanistan.”

“In places like Herat, Iran has significant sway over local issues culturally, economically and also politically. However, for Iran’s ability to expand its western foothold, it will face competition from Russia, China and of course Pakistan. All of them see an opportunity to enhance their vested interests in Afghanistan following any US withdrawal,” he told Asia Times.

This article was originally published on Asia Times

More by Kourosh Ziabari on Asia Times