The American public’s appetite for military intervention has diminished considerably

Kourosh Ziabari – Is the United States still as powerful as it had been 50 years ago? Is it possible for the United States to continue ruling the world, placing dictators in place, staging coups against democratically elected governments and waging unjustified and unsanctioned wars? The brief answer which anyone with some minimal familiarity with the global political equations will give is “no,” but we are not after eliciting an unscientific and unsubstantiated response.

Kourosh Ziabari – Is the United States still as powerful as it had been 50 years ago? Is it possible for the United States to continue ruling the world, placing dictators in place, staging coups against democratically elected governments and waging unjustified and unsanctioned wars? The brief answer which anyone with some minimal familiarity with the global political equations will give is “no,” but we are not after eliciting an unscientific and unsubstantiated response.

We have started a project to explore the different aspects of the decline of American imperialism with the world’s great political scientists and academicians. They join us in exclusive interviews and respond to our questions regarding the prospect of U.S. Empire in an age when the nations have awakened and don’t tolerate the rule of force and tyranny of the hegemons anymore.

The Arab Spring and the courage and audacity the people of countries such as Egypt, Tunisia and Bahrain have showed in standing up against the dictators the United States had installed decades ago is one of the numerous signs that the U.S. hegemony is in decline and will no longer govern the world.

Iran Review conducted interviews with Prof. Francis Shor and Prof. William C. Wohlforth about the decline of the U.S. empire, and this is the third interview in our series of interviews with world’s renowned political scientists about the future of imperialism.

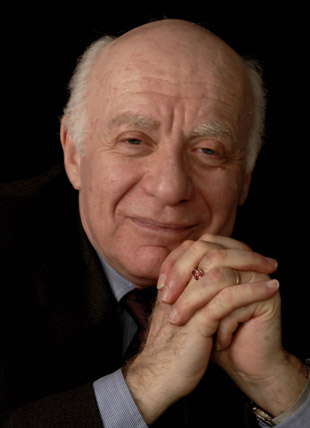

Prof. Michael Brenner is a Professor of International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh and a Senior Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, SAIS-Johns Hopkins. He is the author of several books and over 60 scholarly articles. His essays have appeared on such journals as World Politics, Comparative Politics, Foreign Policy, International Studies Quarterly, International Affairs, Survival, Politique Etrangere, and Internationale Politik.

What follows is the text of Iran Review’s interview with Prof. Michael Brenner.

Q: As you know, the unipolar, hegemonic system of global governance led by the United State constitutes the basis and structure of current international order. However, it seems that a change based on the founding of a power balance against the United States has begun to emerge in the global equations of political power. What’s your analysis of this change and the challenges it poses to U.S. hegemony?

A: The notion of balance of power in the traditional sense is not suited to today’s conditions. The classic world of balance of power, operative roughly from the 17th through the mid 20th century, was conducive to the making, unmaking and remaking of alliances. Changing partners was not promiscuous but commonplace. The enabling features of that ‘system’ were : the considerable number of players several of whom were of approximately equal strength and none of whom towered over the others; military strength determined one’s power; the control of territory was the main objective; and economic relations were largely a zero-sum game. At present, these conditions do not obtain. Moreover, the hallmark of today’s world is the high degree of economic interdependence. Coupled to the primacy of economic well-being in the domestic politics of most countries, there is strong incentive to avoid conflict which could gravely disturb those settled arrangements.

Still, the ability and readiness of powers to form tactical diplomatic coalitions on an issue specific basis is growing. It is commensurate with the decline of American influence. We can expect to see this occurring with greater frequency in the Middle East where American actions are seen by many as a source of disturbance rather than as creating the public good of stability and agreed rules of the road.

Q: It seems that the United States is voluntarily retreating from its position as a global hegemon, which is because of the remarkable increase in the costs of maintaining a unipolar and hegemonic order and the considerable decrease in its utilities. What’s your viewpoint in this regard?

A: The United States will find it very difficult to relinquish the prerogatives of initiative, agenda setting and intervention which it has accumulated. There remains a pervasive belief among members of the American foreign policy community that the United States is the indispensable nation. That belief conforms to the deeply held, uncritical sentiment that it has a mission to perform – a providential or historical one – to lead the rest of the world on the path to enlightenment. Moreover, for many Americans the faith in American exceptionalism buttresses personal self-esteem. This last is important at a time when anxiety and apprehension pervade the collective psyche.

Q: The global capitalistic economy is collapsing and its consequences for the uni-polar and hegemonic order are beginning to appear gradually. What do you think about the repercussions of the global economic recession and its effects on the compasses of the U.S. power?

A: Oddly, the near collapse of the world’s financial system in 2008 led to a strengthening of American influence in the developed world. This is despite the fact that the practices and ideas that brought the world close to collapse originated in the United States. Europe and Japan lack totally the political will to step forward and assert themselves. China is a different story – as we already have seen in the financial sphere. It’s from Beijing that the challenge to American domination of international economic institutions and practices will come.

Q: Based on the emergence and intensification of global resistance against capitalism and liberalism, especially resistance on the microphysical level of global power against the lifestyle of imperialist system, the political power and influence of the United States has been diminishing in the recent years. What’s your take on that?

A: I do not expect that the challenge will be on ideological grounds. The Chinese leadership is utterly uninterested in ideology. The same holds for all those nations that are “making it” economically. This is not to say that there are not significant differences in thinking about macroeconomic management. American ultra-liberalism will have to be amended. However, the basic ideological rejection comes from countries and elites with very little influence.

Q: The resistance and opposition of the United States’ domestic forces against the interventions of the U.S. government in the other countries and the imperialistic traits of the U.S. political system have been contributing to the weakening of the global position of the United States. Would you please share your perspective on that with us?

The American public’s appetite for military intervention has diminished considerably. It is less clear that this is a permanent phenomenon. After all, we’ve seen this after Korea and after Vietnam as well – when it wasn’t lasting. 9/11 gave a particular edge to the disposition of American elites to exploit their greatest asset: the country’s military strength. That fear has abated somewhat. There still remains a readiness to back low-grade military action using Special Forces, drones, etc, That approach lies at the heart of current American strategy to prevent hostile elements from taking power in the greater Middle East, in Central Asia, in Africa and even in Latin America. That cresting capability naturally perpetuates the belief that the United States can shape the affairs of other countries – and do so at a reasonable cost.

This interview was originally published on Iran Review